The Anti-Suffragists came late into the fray. Ever since the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848, when, led by Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women organized to end discriminatory legislation and to press for suffrage, the activists seemed to have defined the terms of the national debate. Yet when the issue came down to votes for women, many women were not enthusiastic about the prospect. Even at the Seneca Falls Convention, of the eleven resolutions passed championing women’s rights, the resolution calling for the vote was the only one not to pass unanimously, and it barely passed at all.

Susan B. Anthony joined the movement in 1851, and although she early sought a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote (the 19th Amendment was, in fact, dubbed “The Susan B. Anthony Amendment”), the Suffragists preferred to gain their objective state by state. There were a number of reasons why the state focused strategy was preferable. First, the Suffragists could concentrate their resources more effectively on individual states rather than trying to win at the national level. Second, they would have more allies at the state level, for that is where the Progressives sought to enact their own reform measures. Third, unlike today, citizens were closer to their state governments rather than to the federal government.

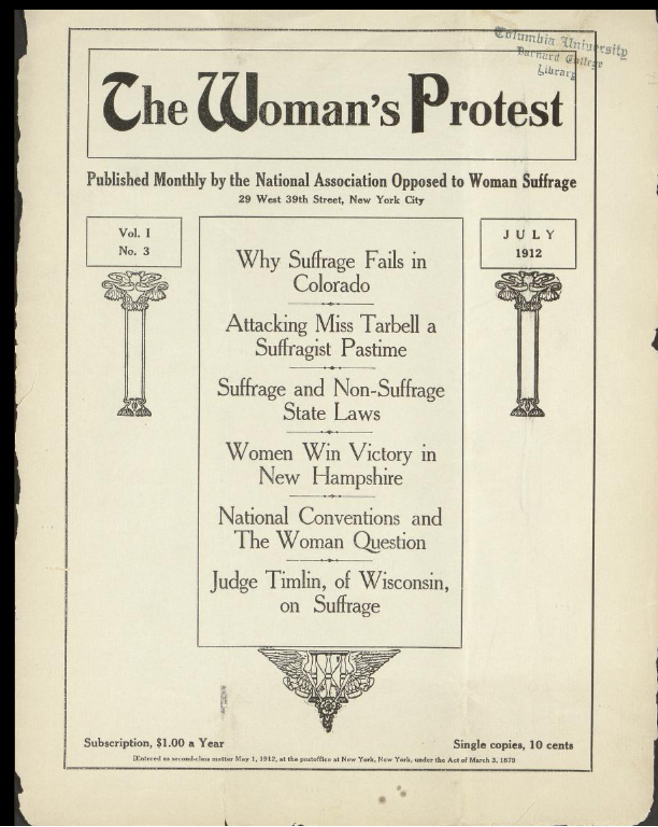

Soon, the Suffragists began to roll up victories in the territories and states of the high plains: Wyoming 1869, 1890; Utah 1870, 1896; Washington 1883; Montana 1887; Idaho 1896. But when they sought victories in Massachusetts and New York, the Anti-Suffragist movement sprang up. In 1882, a group of women “remonstrants” in Massachusetts successfully protested against extending the suffrage for women in municipal elections (women had won the right to vote for school boards in 1879). In 1895, the “Massachusetts Association Opposed to the Further Extension of Suffrage to Women” was formed. 1500 women joined the first year, and the figure doubled the following year, reaching 23,000 in 1914. In 1896, a similar movement and membership arose in New York. Referenda for female suffrage were defeated in both states.

Although the Anti-Suffragists were far less adept politically than their opponents, who had over 30 years of experience behind them, the arguments of the “Antis” struck a chord, particularly among middle class women. Where the Suffragists emphasized the goal of political equality, the Antis spoke to the special “realm” of housewife and homemaker, terms that, by the end of the 19th century, had gained an honorific caché. In the decade of the 1890s, when the opponents of female suffrage began to organize seriously, the phenomenon of “women’s magazines” and “women’s columns” in newspapers appeared, transforming the world of publishing for the public, and seeming to confirm that there were special skills and attributes to the role of the homemaker.

Neither side seemed to consider that the political equality of women and the preservation of their social authority were compatible. The Antis asserted that by bringing women into the “mire” of politics (and the mire of political corruption was everywhere evident at the time), politics would find its way into the home and threaten the protected authority of the woman as mother and homemaker. The Suffragists had long argued that women needed the vote in order to reform discriminatory laws, but the Antis retorted that male legislatures in the states on their own had already removed major common-law detriments and had passed labor laws protecting women.

In Massachusetts, the Antis hit upon a rhetorical device that slowed the momentum of Suffragists. In 1895, another referendum to allow women to vote in municipal elections was defeated 187,837 to 108,974. The Antis had urged women to boycott the vote. In the final tally, 22,204 women had voted in favor of municipal suffrage, while 861 had voted against. But the Antis trumpeted that “only 22,204 women, out of a possible 575,000 qualified to register and vote, voted in favor of municipal suffrage.” The Antis then used the democratic device of the referendum to forestall an extension of the democratic franchise. They called upon states to have referenda on whether the suffrage should be extended to women, with women eligible to vote on the referendum, while the Suffragists opposed such calls and preferred to make progress through the male legislatures.

By 1910, the Suffragists had been able to overcome the tactics of the Antis and more states began to allow for partial or full voting rights for women. By the time World War I began, most of the Republican states had accorded the right to vote to women, while the majority of the Democratic states remained stolidly opposed. It was at this point that the need for a constitutional amendment became manifest. The 1916 Presidential election was emblematic. The Republican candidate, Charles Evans Hughes–former Justice of the Supreme Court and Governor of New York—supported universal female suffrage, while President Woodrow Wilson equivocated.

A third voice had entered the debate. The activist, Alice Paul, whose story is adroitly told by Professor Kevin O’Neill, engaged in picketing and demonstrations that focused particularly on the White House and President Wilson, who finally came around to supporting an amendment. Both the Suffragists and the Anti-Suffragists deplored her tactics, but Paul had learned her activism in England from a more militant suffrage organization.

In the end it was not so much Paul’s demonstrations that gained the victory though they had an effect, but it was the debate that the American Suffragists and Anti Suffragists had engaged in that laid the groundwork. In 1919, by the time that Congress sent the 19th Amendment to the states to be ratified, only eight states had no provision at all for female suffrage. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee, by a one vote margin, became the 36th state to ratify the Suffrage Amendment.

Millions of women voted in the 1920 election and gave Warren G. Harding one of the greatest popular vote victories in American history.

Shortly before Tennessee’s vote was held, Warren G. Harding accepted the nomination for President at the Republican Convention in Chicago. Harding was a man whose capaciousness would free prisoners of conscience; he would affirm that the black citizens of America should be “guaranteed the enjoyment of all their rights;” he would seek to “stamp out lynching and remove that stain from the fair name of America;” and he would welcome the Socialist Eugene V. Debs to the White House.

Harding had long supported the Susan B. Anthony Suffrage Amendment. To the nation, he declared,

Enfranchisement will bring to the polls the votes of citizens who have been born upon our soil, or who have sought in faith and assurance the freedom and opportunities of our land. It will bring the women educated in our schools, trained in our customs and habits of thought, and sharers of our problems. It will bring the alert mind, the awakened conscience, the sure intuition, the abhorrence of tyranny or oppression, the wide and tender sympathy that distinguish the women of America. Surely there can be no danger there.

And to the great number of noble women who have opposed in conviction this tremendous change in the ancient relation of the sexes as applied to government, I venture to plead that they will accept the full responsibility of enlarged citizenship, and give to the best in the Republic their suffrage and support.

Freedom of speech had enabled the great debate on women’s suffrage. The debate had ended, and it ended well.